PROJECT OVERVIEW

STANDING TOGETHER: Inez Milholland’s Final Campaign for Women’s Suffrage

[A visual essay by Jeanine Michna-Bales, 2016-2020;

research from 2016 - 2020 and principal photography from 2018 to 2020]

While researching the underground railroad, I came across the beginning history of the American Women’s Suffrage Movement in the likes of Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass. These people sat in the back of my mind until 2016 when I started to actively look into the movement. I stumbled across original letters of the Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana at the William H. Smith Memorial Library at the Indiana Historical Society. The suffragists were attempting to gain the right to vote in Indiana and were asking for a special session of the state legislature. They had initiated a letter writing campaign aimed at every influential man across the state. The letters included a pledge card to sign and return in support of the cause. I was shocked as I read through the replies. Though there were quite a few letters and pledge cards returned in support, there were many in dissent. It was fascinating to see such broad stereotypes about women handwritten in beautiful script across the pages with a proud signature at the bottom. I was hooked.

As I continued to teach myself about the Suffrage movement, I quickly realized the incredible twists and turns of this epic battle in our country’s history were not widely known. How could I gain access to this important socio-political fight and create a visually compelling narrative that would bring this story out into the open?

It was then that I learned of a little-known champion who was at the forefront of the suffrage movement in the early 20th century, Inez Milholland Boissevain (1886 – 1916). The more I read about her, the more fascinated I became with her life, her passion, her ideals and her determination.

Inez and her sister Vida were born into a well-to-do family who lived in England and Germany before eventually settling back in the United States. Their father was John Milholland, a newspaper editorialist and a reformer with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Inez was exposed to the English suffrage movement through the many dinner guests and visitors to her parents’ home while they were living in London. She first began working for suffrage while still a student at Vassar college when she formed a suffrage society made up of two-thirds of her classmates. Since discussion was forbidden on campus by Vassar President Taylor, meetings were held just off campus.

By profession, Ms. Milholland was a practicing lawyer in New York state. She attempted to enter Yale, Harvard and Columbia University law schools, but was denied admission because she was female. She obtained her law degree from New York University School of Law. At the beginning of WWI, Milholland became a war correspondent, but was denied access to the front lines due to her gender.

In 1913 her marriage to Dutch businessman, Eugen Jan Boissevain, caused her to lose her American citizenship and forced her to become a citizen of Holland. Eugen offered to go through the naturalization process in order for her to still be able to vote. She refused and said they would get the law changed.

Inez Milholland Boissevain, wearing white cape, seated on white horse at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington D.C., Bains News Service Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

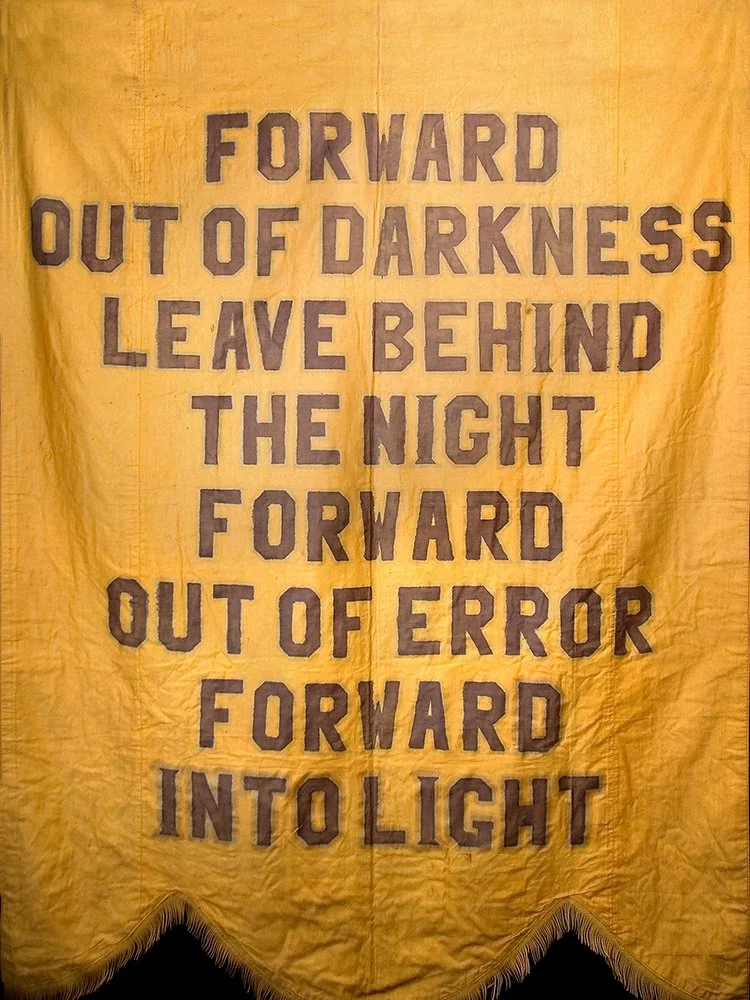

Alice Paul recruited Milholland to the National American Woman Suffrage Association Congressional Committee and she soon became a famous symbol of the suffrage movement. She inspired crowds with her powerful speaking ability and distinguished herself astride a white horse at the National Woman Suffrage parade in Washington D.C. in 1913. When the even descended into chaos and violence, Inez courageously rode “Grey Dawn” through the crowd to keep the parade going while carrying a banner that became synonymous with her name [pictured to the left].

The suffrage movement was rife with infighting. Various groups were advocating for different strategies; from a state-by-state versus a national approach to how far to go beyond the vote into other women’s rights. As egos clashed and various organizations fought over strategies, race, and temperance the decades stretched on with little gain.

In 1916 women were over 60 years into the battle of the American Suffrage Movement. Frustrated by President’s Wilson’s inaction on the matter, a group of suffragists decided to put their fate directly into women’s hands. The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, or as it became known more commonly The National Woman’s Party, came up with a radical campaign to send hundreds of suffragists from the East out to the 12 western states where women had the right to vote. Their request was a simple one; put aside all political agendas and cast a protest vote against President Wilson and his fellow Democratic Congressman.

Women from the east including Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others joined with their western counterparts and covered specific states. Inez Milholland was appointed special “flying envoy” to make a 12,000-mile swing through the west in October leading up to the 1916 Presidential and Congressional election in early November.

Traveling with her sister Vida, Inez delivered some 50 speeches in eight states in 28 days. Battling chronic illness and lack of sleep, her four-week itinerary, brutal even by today’s travel standards, consisted of street meetings, luncheons, railroad station rallies, press interviews, teas, auto parades, dinner receptions, speeches in the West’s grandest theaters, and even impromptu talks on trains while on her way to the next destination.

On October 24th, 1916 her last public speech was delivered at Blanchard Hall in Los Angeles. She collapsed on stage and her final public words were, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” Her health forced her to cut the tour short and she died 30 days later at the age of 30, making her the sole martyr of the American Suffrage Movement. Inspired by her devotion, the movement continued to grow, and ultimately led to the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment.

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Standing Together retraces the sisters’ journey as a determined Inez persuaded standing-room-only crowds throughout the west to vote for the enfranchisement of women.

The visual essay is pieced together using many primary sources and the research directly informs the image choices throughout the series. In her letters to her husband, Eugen, Inez discussed her speeches, how she was “doctoring” herself to get through the tour and described in detail the Western landscape she was seeing and expressed a wish to return to some of the places with him.

“Friday 11:15 am on the train to Cheyenne

Dearest,

Well, I am seeing the West, and it is very wonderful. But I am glad that I am only going to have a hurried glimpse of it. I want to really explore it with my lover.

It is absurd and inadequate for me to see beautiful things without you.”

As I drove and rode a train through the places that she visited, I envisioned what she had described through my camera lens. I purposefully chose to depict the landscape images as she might have seen them.

For the images presented as reenactments, I chose to visually present them as “Autochrome" Lumières”, created by the Lumière brothers in France, which was the principle color photographic process in use at the time.

To emphasize the important fact that Inez and her fellow suffragists ultimately won the vote for all women in America (although in some states not until 1965 or later), I asked different women from all walks of like and of all ages to stand in for Inez and her fellow suffragists.

“A triumphant threatening Army of white States … “ 1914 map of Woman Suffrage in the United States, Smithsonian Institution